The human spine is a masterpiece of biological engineering—a flexible, sturdy column of 33 vertebrae designed to support our weight, protect our spinal cord, and allow us to twist, bend, and move. But like any complex mechanical system, things can sometimes shift out of alignment.

One of the most common, yet frequently misunderstood, causes of chronic back pain is Spondylolisthesis.

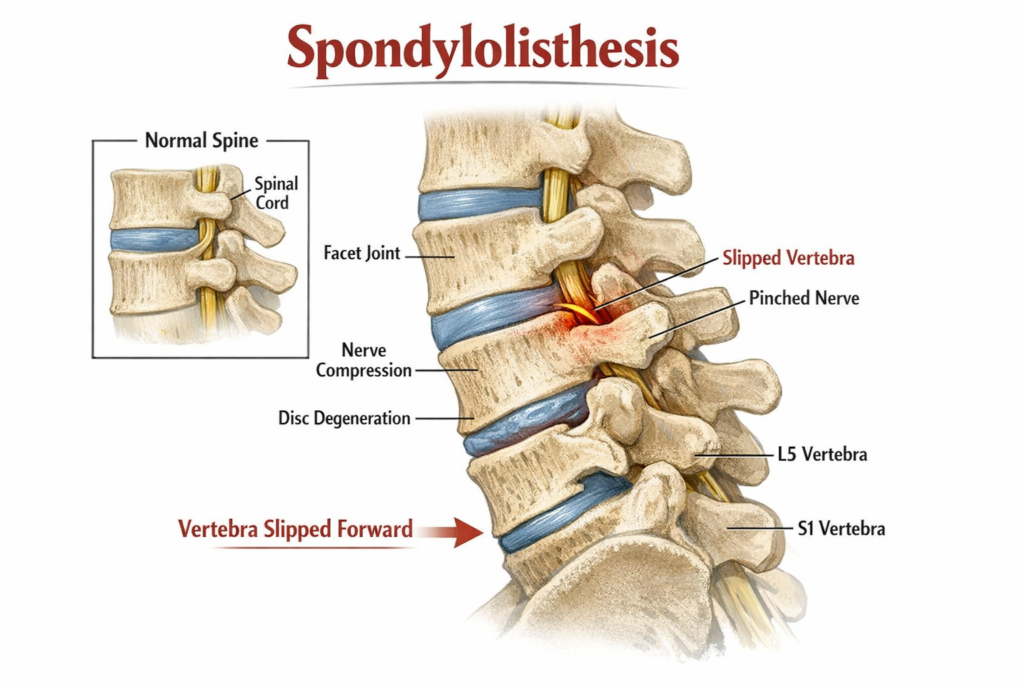

The term sounds intimidating, but the concept is straightforward: it occurs when one of your vertebrae slides forward (or backward) over the one below it. This “slip” can lead to a cascade of symptoms, from dull muscular aches to sharp, radiating nerve pain.

In this comprehensive guide, we will break down everything you need to know about spondylolisthesis—from its mechanical causes and varied types to the cutting-edge treatments available today.

1. What Exactly is Spondylolisthesis?

At its core, spondylolisthesis is a condition of spinal instability. To understand it, we have to look at the anatomy of a vertebra. Each bone in your spine has two “facet joints” in the back that link it to the bones above and below, keeping the column stacked neatly.

When the structures that hold these bones in place—be it the joints, the ligaments, or the bone itself—become weakened or damaged, the vertebra can no longer resist the natural shear forces of your body weight. It begins to migrate.

Spondylolysis vs. Spondylolisthesis: The Difference

It’s easy to confuse these two terms.

Spondylolysis is a stress fracture in the pars interarticularis (a thin bridge of bone in the vertebra).

Spondylolisthesis is the actual slipping that often happens as a result of that fracture. Think of spondylolysis as the crack in the foundation, and spondylolisthesis as the house shifting because of it.

2. The Five Main Types

Not all slips are created equal. Doctors categorize spondylolisthesis based on how and why the slippage occurred:

This is the most common form, often appearing in teenagers and young adults. It is usually the result of spondylolysis (the stress fracture mentioned above). Athletes involved in sports that require frequent overextension of the back—like gymnastics, football, or weightlifting—are particularly prone to this.

II. Degenerative Spondylolisthesis

As we age, our intervertebral discs lose water and elasticity, and our ligaments weaken. This is the “wear and tear” version of the condition, most common in adults over the age of 50. It occurs because the stabilizing structures simply can’t hold the alignment anymore.

III. Congenital (Dysplastic) Spondylolisthesis

Some people are born with a vertebral abnormality—a malformed facet joint, for instance—that makes the spine naturally less stable. Over time, gravity and movement cause the vertebra to slip.

IV. Traumatic Spondylolisthesis

This is caused by a sudden, high-impact injury. A car accident or a severe fall can fracture the bony structures of the spine, forcing a vertebra out of position instantaneously.

V. Pathological Spondylolisthesis

The rarest form, this occurs when the bone is weakened by a systemic disease, such as a tumor, an infection, or certain bone disorders (like Paget’s disease), making it unable to support the spinal load.

3. Recognizing the Symptoms

nterestingly, many people have Grade I spondylolisthesis and never even know it. However, when symptoms do appear, they typically include:

Localized Low Back Pain: Often described as a deep ache that worsens with activity or standing for long periods.

Hamstring Tightness: This is a classic “tell.” People with this condition often have incredibly tight hamstrings and a stiff, “waddling” gait.

Sciatica: If the slipping bone pinches a nerve root, you may feel sharp, shooting pain, tingling, or numbness traveling down your buttocks and into your legs.

Spinal Stenosis Symptoms: In degenerative cases, the slip can narrow the spinal canal, leading to heaviness in the legs when walking.

4. Treatment Options: From Conservative to Surgical

The good news? The vast majority of people with spondylolisthesis (especially Grades I and II) do not need surgery.

Non-Surgical Management

Physical Therapy: The primary goal is “core stabilization.” By strengthening the deep abdominal and back muscles, you create a “natural corset” that supports the spine.

Activity Modification: Avoiding heavy lifting and hyperextension (arching the back) during the healing phase.

NSAIDs: Medications like ibuprofen to manage inflammation.

Epidural Steroid Injections: If nerve pain is severe, a targeted injection can reduce inflammation around the pinched nerve to provide relief.

When is Surgery Necessary?

Surgery is usually reserved for patients with Grade III slips or higher, or those whose pain has not improved after 6+ months of physical therapy.

The most common procedure is a Spinal Fusion. In this surgery, the surgeon uses hardware (screws and rods) to hold the vertebrae together and places a bone graft between them. Over time, the two bones grow into one solid piece, stopping the slippage forever.