For a dedicated runner, a diagnosis of a herniated disc feels like a sentence to the sidelines. The sharp, radiating pain of sciatica or the dull ache in the lower back isn’t just a physical hurdle; it’s an emotional one. When your identity is tied to the rhythmic strike of pavement and the clarity of a “runner’s high,” being told to “rest” can feel like losing a limb.

But does a herniated disc mean you have to hang up your laces forever? Or is it time to embrace the “glide” of the elliptical trainer? To answer this, we need to look at the mechanics of the spine, the nature of impact, and how to listen to the signals your body is desperately trying to send.

Understanding the "Slip": What’s Happening in Your Spine?

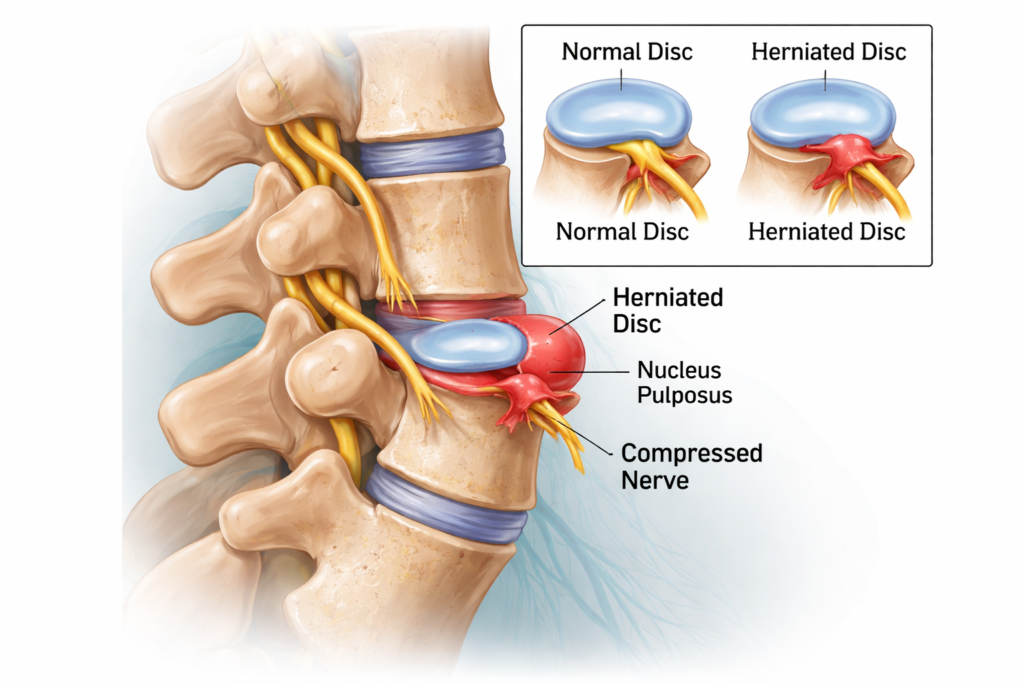

Before we talk about miles and heart rates, let’s get the anatomy straight. Your spinal discs act as shock absorbers between your vertebrae. They have a tough outer layer (the annulus fibrosus) and a jelly-like center (the nucleus pulposus).

A herniated disc occurs when a tear in the outer layer allows some of that inner “jelly” to push out. This protrusion can press against spinal nerves, causing:

Sciatica: Sharp pain radiating down the leg.

Numbness or Tingling: Often felt in the feet or calves.

Muscle Weakness: A feeling that your leg might “give out.”

The Impact Factor

Running is a high-impact activity. Every time your foot hits the ground, a force equal to 2.5 to 3 times your body weight travels up through your legs and into your spine. If your discs are healthy, they handle this like a high-end suspension system. If a disc is compromised, that repetitive loading can exacerbate the protrusion or irritate the already inflamed nerve.

Running with a Herniated Disc: Is it Ever Safe?

1. The Acute Phase (The "No-Go" Zone)

If you are currently experiencing sharp, shooting pain, or if your back is “locked up,” running is a hard no. In this stage, the inflammation is at its peak. Any high-impact movement risks turning a small herniation into a major one.

2. The Recovery Phase (The "Grey Area")

Once the sharp pain subsides and you’re left with a dull ache or occasional stiffness, you might be tempted to test the waters. This is where most runners make the mistake of doing too much too soon. Safety here depends on core stability. If your “inner corset” (the deep abdominals and multifidus muscles) isn’t firing, your spine takes the full brunt of every stride.

3. The Maintenance Phase (The "Green Light")

Many runners return to the sport after a herniation. If you have full range of motion, no neurological symptoms (numbness/weakness), and have cleared a physical therapy screening, running can actually be beneficial. Research suggests that controlled, upright movement can help “pump” nutrients into the discs through a process called imbibition.

The Case for the Elliptical: The Runner’s Best Friend?

If you aren’t ready for the pavement, the elliptical is often hailed as the ultimate compromise. But is it actually better?

The Pros:

Zero Impact: Your feet never leave the pedals, meaning that 3x bodyweight shock is eliminated. This allows you to maintain cardiovascular fitness without “pounding” the injured disc.

Closed-Chain Movement: Because your feet are fixed, there is less shearing force on the joints.

Upright Posture: Unlike cycling, which requires a “hinged” or hunched position that can aggravate some herniations, the elliptical keeps the spine in a relatively neutral, upright position.

The Cons:

- The “Twist”: Some elliptical machines have a wide pedal stance or a motion that encourages excessive hip rotation. If your herniation is sensitive to twisting (rotational shear), the elliptical might actually cause more discomfort than a straight-line walk.

- The Boredom Factor: Let’s be honest—it’s not the trail. Mental fatigue can lead to poor form, which can lead to back pain.

The "Red Flags": When to Stop Immediately

Physical discomfort is part of being an athlete, but “nerve pain” is a different beast. You must stop your workout and consult a doctor if you experience:

Saddle Anesthesia: Numbness in the groin or “saddle” area.

Sudden Weakness: Your foot slapping the ground (foot drop).

Pain that Improves with Rest but Spikes with Movement: This indicates the disc is still actively pressing on the nerve.

Loss of Bladder/Bowel Control: This is a medical emergency (Cauda Equina Syndrome).